The role of traditional family system in perpetration of sexual and gender-based violence in Africa

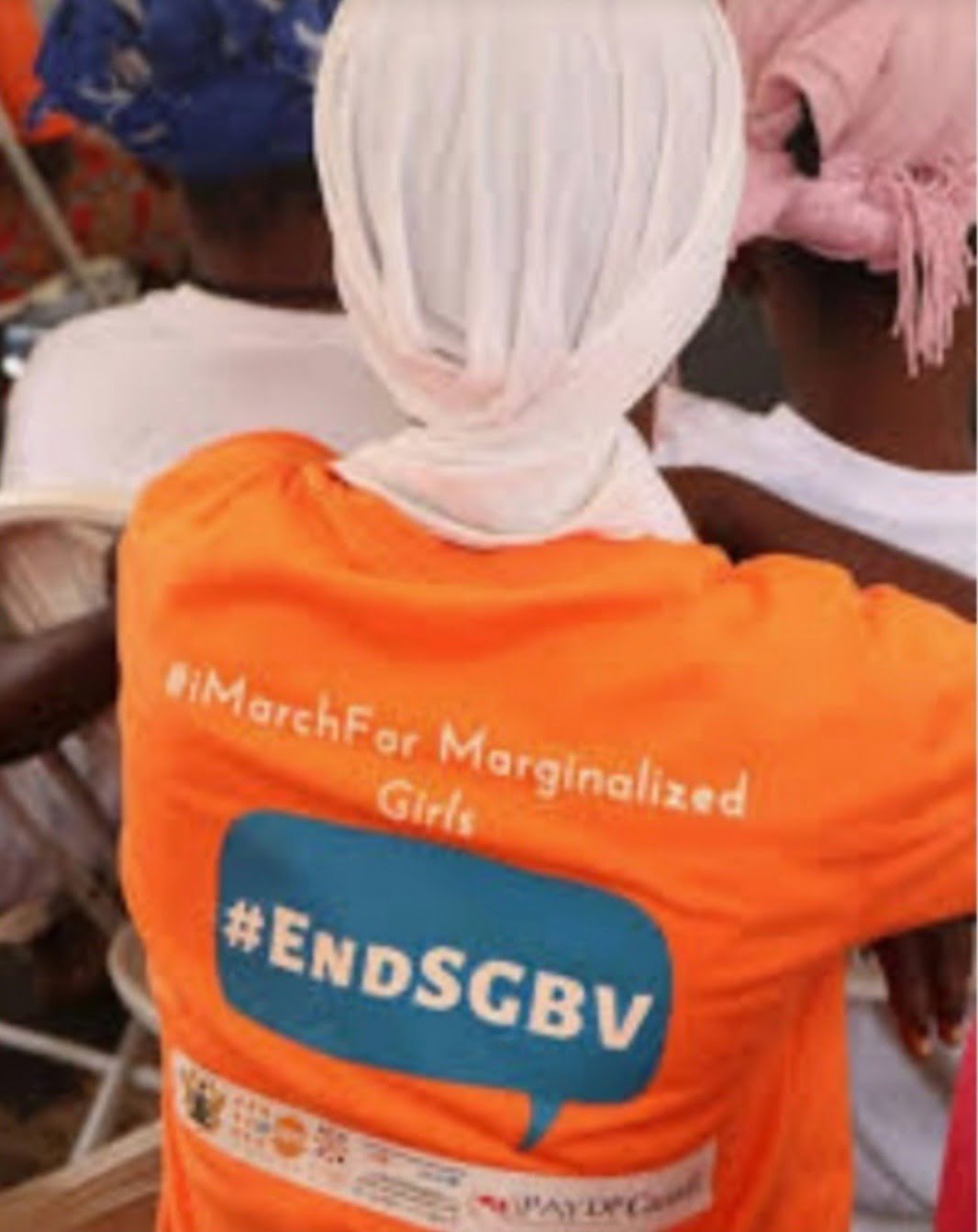

Sex and Gender-Based violence (SGBV) is an abuse meted on individuals by virtue of their sex or the role ascribed to them in society.

In Ghana, sexual offences is captured in Chapter Six of the Criminal Offences Act, 1960 (Act 29) and it covers “any unlawful dealing with a female by way of rape, defilement, and in the case of unnatural carnal knowledge, the victim could be either a man or woman, indecent assault (man or woman) and again, incest.”

Traditionally, males have been taught to act strong and ruthlessly in an event of any confrontation and should never appear weaker especially to the female party.

Therefore it’s even unheard-of in some communities for a male to cry; this is evident in some existing proverbs in the Ghanaian community such as ‘Berima Nsu’ in the Akan society, translated as a ‘man does not cry’.

In some other places, in any given unpleasant discuss or tussle between a male and a female, the male is always deemed right; similarly, young ones in the Ghanaian society have been historically thought to unquestionably obey every order of the elderly, such practices have gone a long way to entrench SGBV against vulnerable people as girls for instance are unable to refuse calls from the elderly.

Though Article 11 of the 1992 Constitution accommodates customary laws and though customary laws generally considers sexual and gender based violence unlawful, it appears what pertained and still pertains in practice in the traditional environment is somewhat different from what is accepted in principle; no wonder SGBV issues have now been particularly isolated as a preserve of the country’s criminal legal system.

However, notwithstanding the fact that SGBV cases are now to be strictly handled by state authorities, the family/ clan heads (chiefs and elders) who normally happen to be males in almost every community and have among their many responsibilities the task to mediate in all manner of cases, appear to be the arbiters and judges in SGBV issues confronting their clans.

In fact some sections of the society/ community members rooted in the traditional system continue to look up to the ‘abusua panyin’ (clan head)/Chiefs for guidance and direction in SGBV cases as they frown on the actions of individuals who immediately resort to legal actions in SGBV cases at the expense of the traditional channel of adjudicating issues because they usually describe such matters as ‘issues of the home’.

Parents or guardians who may have naturally resorted to legal redress are stifled by local community practices, thus causing them to conform to the generally accepted community standards.

In view of the situation, community leaders by default are allowed by some unsuspecting police personnel to even withdraw already reported cases at police stations back into their domain for redress, with or without the consent of the victim.

The question therefore is, assuming without admitting that the family system should be the first point of call in such rights abuse cases, how do they handle such issues when they encounter them? Many of these leaders potentially act or would act partially.

Most of these leaders who are males hold a view that women are to be subservient to men, as such, women must endure any abusive conduct, and women should refrain from provoking men to violence.

This echoes an old established impression that women “asked for” and therefore “deserved” acts of sexual violence. With such a mindset, we could hardly make any headway in ameliorating or eliminating SGBV.

We should also note that it is no hidden secrete that some chiefs/clan heads deliberately connive with perpetrators who act erroneously, basically for their individual selfish gains which could be in the form of financial or material benefits.

In some bizarre instances, such cases are even resolved with the payment of liquor rather than securing justice and a well deserving compensation for victims.

The twist of events only subject victims to further violence in future as local setup fail to protect them.

In a past research work conducted on domestic violence in Ghana (name of researcher and year, if readily available?), although the Chiefs interviewed asserted that they would refer domestic violence and by extension SGBV cases to the police when they occurred, they conflicted their earlier stance by recounting how they amicably settled horrendous criminal cases.

Therefore, we must not pay lip service and presume leaders of the traditional setup now fully understand the ramifications of their actions since no substantial research work has come out to present new facts in favour of changing attitudes of traditional leaders.

This why it is important that we take a critical look at how our traditional societies currently handle SGBV cases and begin to work at making our traditional and family leaders responsible through education, punitive actions and other deterring measures so as to make it unattractive for them to adjudicate criminal cases involving SGBV.

It is important to note that, so far as there are incentives provided by offenders to compromising leaders, the fight against SGBV is a long way ahead.

By Joseph Ankamah

The writer is the General Secretary of the Human Rights At Law Forum (HRALF)

Good Grow: The Marijuana Farm Founded by Akufo-Addo’s Daughters

Good Grow: The Marijuana Farm Founded by Akufo-Addo’s Daughters  National Food Suppliers for Free SHS set to picket at Education Ministry

National Food Suppliers for Free SHS set to picket at Education Ministry  Information Ministry justifies ¢151k paid to staff as Covid-19 risk allowance

Information Ministry justifies ¢151k paid to staff as Covid-19 risk allowance  I’ll help farmers with tractors to increase productivity – Bawumia promises

I’ll help farmers with tractors to increase productivity – Bawumia promises  CETAG meets national teaching council to conclude on strike

CETAG meets national teaching council to conclude on strike  Adom Kyei Duah cannot be the Jesus that Christians seek – Christian Council of Ghana

Adom Kyei Duah cannot be the Jesus that Christians seek – Christian Council of Ghana  Bawumia’s smartphone pledge misguided and visionless – Adongo

Bawumia’s smartphone pledge misguided and visionless – Adongo

👍🏾Very comprehensive and insightful article that covers the key elements of the issue of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence.

A very well researched and comprehensive article that addresses the key issues in Sexual and Gender-based violence.

A must read.